PART I: In an Uncivilized Debate about Cultural Appropriation…

I grew up about ten miles from the University of Illinois (U of I). The U of I began in 1867, roughly fifty years after the state was formed. The official mascot of the U of I was the “Fighting Illini”, a representation of the Illinois Confederation of indigenous Peoples (about a dozen tribes) known as the “Illiniwek”. The Illiniwek, who numbered over ten thousand in the 17th century, were more or less gone by the early 19th century. The few hundred who remained reportedly joined the Peoria Tribe.

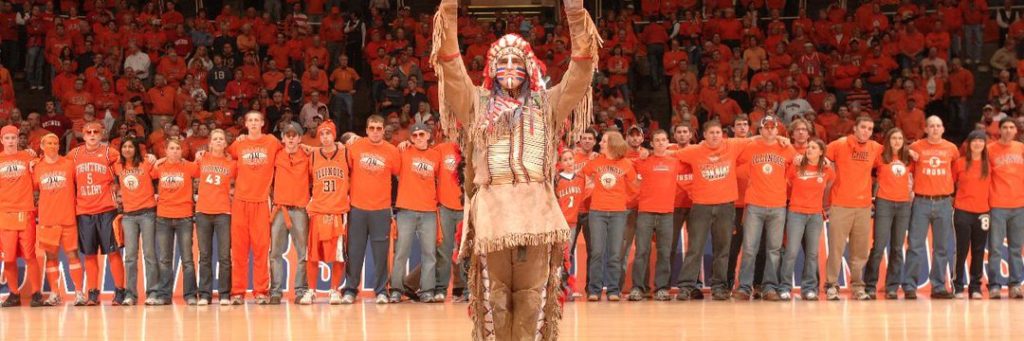

However, “Chief Illiniwek” to me was the name of the school mascot. The U of I had been the “Fighting Illini” since 1926 and “Chief Illiniwek” was the guy who—as far back as anyone could remember, and with a very rousing marching band tune behind him—would dance an authentic, “ceremonial Indian” dance at halftime.

It turns out, the dance was actually invented by the first few students to perform as “The Chief”, back when the tradition started. I just recently discovered that they learned it, indirectly, in the Boy Scouts, from that organization’s handbook, in the section drafted by Ralph “Doc” Hubbard.

Doc Hubbard was a noted cultural archivist/preservationist who eventually taught at what is now Minot State College. In his life, Hubbard created museums devoted to preserving Native American culture. He was a native New Yorker born on a Seneca reservation, but, by blood, was actually 1/8th from a different tribe, the Mohawk. He reportedly had a life-long interest in learning and passing on the knowledge of Native American culture.

By the time I had grown, moved away, started my own family, and ultimately returned to the area in my thirties, it was the turn of the century and a vocal group of people had been protesting The Chief for over a decade. This was part of a nationwide movement to stop the commodification and offensive use of all the iconography around marginalized cultures. That movement continues to this very day. And it isn’t done yet.

It seems straightforward now. Back then, though, it wasn’t obvious to everyone what the correct call was. For example, in the mid-90s, even the leader of the Peoria Tribe of Indians (the last vestiges of the actual Illiniwek, you’ll recall) said in an interview that he was proud of the university’s use of The Chief.

Now, if you’ve never seen the dance in question, I will offer that it was very exciting. In its given context of the sporting events, it was even more electrifying for the fans. I think it made most of the (mostly white, rural) folks feel like they were part of a long tradition. Even the much more diverse student population agreed. Time and time again, as the U of I students were polled about their feelings, an overwhelming majority (69%, for example, in ’04) wanted to keep it.

I was never a U of I student (although I worked for the University around this time). As I said, I was a townie. But, since I had grown up there and had been imprinted with the tradition of The Chief, I admit I was torn about it for a while. Finally (for me), during a visit early in the aughts, filmmaker and activist Michael Moore put it into stark relief. I’m paraphrasing, but he said—Look, the Illiniwek were either infected or slaughtered by the White Man. So, how would you feel about the “University of Dachau Fighting Jews”…with a guy in leg chains coming out and dancing at halftime?

Still, by the mid-2000s it was clear that it wasn’t going to happen naturally. It would have to be forced. A 2005 ban on the U of I hosting any post-season sporting events by the NCAA until the school removed all of the Chief nonsense did the trick. By March of 2007, the Chief had danced his last dance.

I mention all of this because, in the intervening fifteen years, the idea of any non-indigenous person or group putting on Native American ceremonial headdress and dancing around for profit or as entertainment has become the exemplar of misuse of another culture. And that is correct. Of course, it is inappropriate and disrespectful to cash in on the name and iconography of Native Americans. Full stop.

This is analogous to how it is inappropriate for the University to have been making millions of dollars off of the backs of the (mostly minority) student-athletes, using their talents in the pseudo-feudal sports business. Or, widening our scope further: Just last year, the U of I student government passed a resolution in favor of an anti-Israel BDS (boycott/divestment/sanctions) resolution in protest of the university doing business with companies that profit from human rights violations in Palestine.

The United States Supreme Court has opened the door for student-athletes to be reimbursed for their image/likeness; but, there has been no real movement in the BDS front. This all draws the point: These things take time.

Back to The Chief: speaking of time, during those 80 years—largely before the internet and before society was really allowing marginalized people to participate at all—many things that are seen as outrageous now, were really the only exposure to those cultures. If I—say, for the sake of argument—found out that I was 1/8th Lakota Sioux, and got worked up by the innate beauty of The Chief’s dance, and then as a kid visited a Native American Museum created by Doc Hubbard, and then watched countless Lone Ranger shows with its stereotypical portrayal of Tonto—even as a child, I was precocious enough to recognize that Tonto was the Prime Mover of that story—and all of this bubbled inside me so much as to make me stories of Indigenous peoples a facet of my own speculative fiction, is that not a good thing?

Should cultural outputs (like Art, for example) be judged on their own merits, or should there be a gatekeeping function in place to keep the non-marginalized peoples from creating or even attempting to experience marginalized cultures? Would so many people enjoy Blues music today if Elvis, The Beatles, and The Rolling Stones, and all the rest had been somehow not been allowed to hear, sample, co-opt, and synthesize new versions of music from other cultures? Would Rap music have supplanted Rock as the most popular music without Vanilla Ice and Eminem, aided and abetted by MTV and the music industry at large?

Do white anglos commit cultural appropriation when they open an Asian-themed restaurant in San Francisco? What about when you take into consideration that so-called “Chinese Restaurants” in our various American urban ‘Chinatowns’, usually pan-Asian owned and operated, aren’t really serving food that anyone in China would recognize as being from their culture, anyway?

It all gets confusing, doesn’t it?

As a white male writer, am I really, truly, committing cultural appropriation by having a non-white, or female, main character? What if that character performs a song in the story from a religion that I don’t belong to? What if my story’s system of magic also has a deep relationship to all religions in my world-building? When I did that, did I appropriate every culture with a religion on the entire planet, all at once?

Some would say yes.

For me, I suspect some line-drawing is in order. First, I should answer the question: Just what is cultural appropriation?

—–

An analysis of the arguments over Cultural Appropriation will appear tomorrow in PART II of IV.

*- Feel free to email me for citations to any assertions of fact