The Universe™ really does have a way of showing you, doesn’t it?

Only a few hours ago, I was still swimming in my typical holiday/year-end blues. This year it was exaserbated by the ongoing End of the World™ (which—spoilers—turns out to be equal parts: environmental collapse, plague, and impending fascism) and I was topping it all off by fretting that I lacked the impetus to publish some kind of “2021 Wrap-up” blog post. Because, you know, the only thing better than a diary entry as self-therapy is feeling guilty for not doing one!

And, just as for many others, for me this was all amplified by the dread arrival of 2022; this is because, like the joke goes, it always looks darkest right before it goes completely black.

Then I was forcibly refocused: I found out that one of my personal heroes, the great Andrew Vachss, had just died.

So, at least now I know my topic.

It isn’t an overstatement to say the man’s life was a study in heroism. During his formative young adult years—before becoming an attorney who represented strictly abused children—he held other front-line positions in child protection. He was a humanitarian aid activist in the Biarfran War, an U.S. Federal Investigator for STD tracking, and also a New York City social-services caseworker. He started and ran a self-help center for urban migrants in Chicago and directed a max-security prison for violent juvie offenders.

That was where he got the meat for his 1973 novel A Bomb Built in Hell. It was rejected by every publisher, one of whom described it as a “political horror story.” Others berated it for its “lack of realism”. But, get this:

…The subject matter was a child who entered his high school for the purpose of killing everyone.

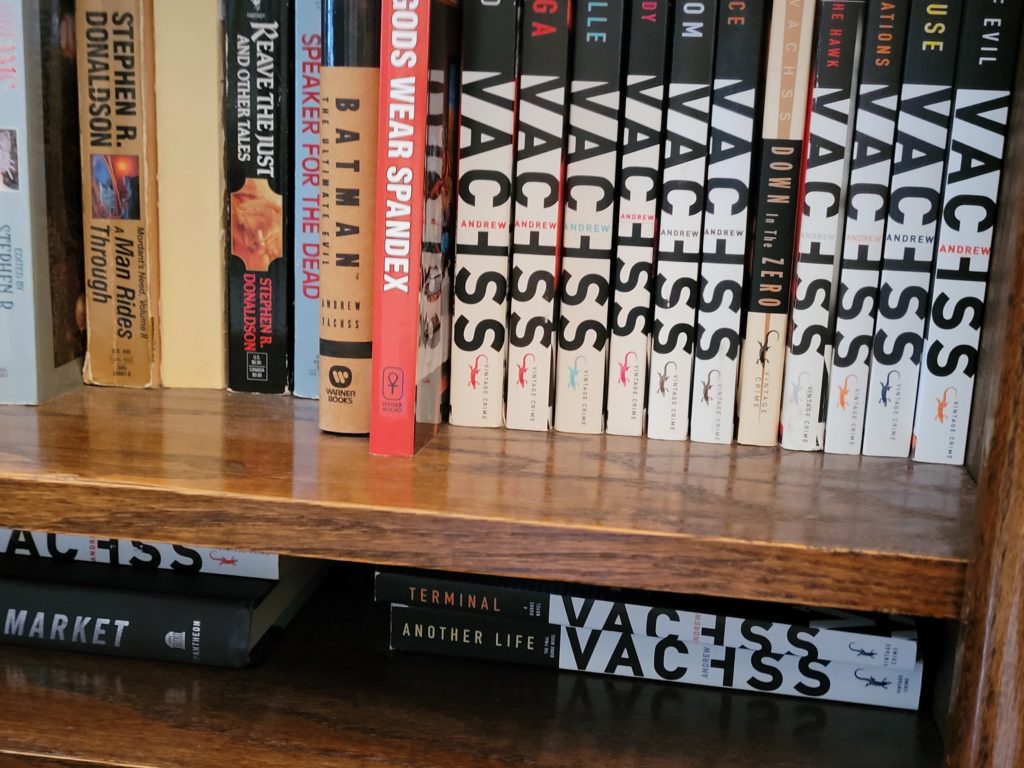

This no doubt set the course for the rest of his life’s work. As I mentioned, after graduating law school top of his class, he became an attorney. Naturally, all of his fellow students thought he was crazy when he said he wanted to represent children—except for one, who became his partner. Their law practice was largely underwritten by the proceeds of his crime novels:

Specifically, that was the “Burke” series, which continued to lay bare the underbelly of crime that actually was “true.” He often said his secret was that he wasn’t making up the subject matter so much as he was reporting it. To say his gritty noir fiction was dark is a true understatement. His crisp prose descriptions of ethical gray areas always read like a knife to the throat.

The key was that his writing was always a “trojan horse” designed to outrage the reader about the culture of child abuse that we all live with. In a brain fogged world where “rape” is called “fondling,” his novels dared you to remain ambivalent.

His success as an author and the attendant celebrity he gained helped him arrive on a couple of episodes of “Oprah” as they both championed The “National Child Protection Act of 1993”.

His website is a testimony to his work, and especially his focus on being what he called a soldier in the only Holy War worthy of the name. He, naturally, says it better than I could:

“The people who care about kids are not focused. They are not a single-issue constituency—unlike the people who care about, say, guns. Or the people who care about, say, not allowing abortion. Those people are hyper-focused. Those people represent a deliverable bloc of votes with which any politician can be threatened.”

My interactions with him 100% confirmed his focus. Always by email, and always after an intermediary had vetted me as a potential ally, he shared some thoughts with me. Among that first was that, by using a “Yahoo!” email, I was supporting a corporation that aided and abetted China in human rights abuses against children. He was always, always, focused on that.

How he managed to maintain that focus, that fire, for so long was amazing.

Which brings me back to the blues. His novels also almost always featured Blues music—which was appropriate with its juxtaposition of the melancholy that comes with hopeless causes and the celebration of the fight itself. From his book Dead and Gone:

The crowd was insane … and under control. His control. He was dealing for real, and the crowd was in his hands—spontaneous reaction to spontaneous combustion. As he teased an impossible run of unreal notes out of the steel slide, a thickbodied man in a yellow silk shirt stood up and yelled out, “That’s the real thing, brother!” as if he were waiting on a challenge.

You could almost see the notes flow out of that black guitar—a liquid ribbon of honey and cream, draped over concrete and barbed wire. For a slice of time, I was transported. Lost in the truth. Feeling … connected to something more than me and mine. I reached for a cigarette. Came up empty. Zeffa was next to me, on my left. Her hand dropped to her purse. She flicked it open one-handed, pointed to a pack of Carltons. The pack was right next to what else she was packing—a dull-black Glock.

I thanked her with a nod. Lit the smoke. Took a deep drag. It tasted like crap, no hit at all. I put it in the ashtray and let it burn down.

The man with the black guitar finished his set … barely. The crowd kept demanding “One more!” and he kept going with it.

Finally, he just bowed slightly, touched the brim of his hat, and stepped off the stage and out the back.

“Son Seals!” the announcer shouted, as the man walked off with his black guitar.

“Come on,” Zeffa said.

We followed her to a basement where ratty old couches were stacked against one wall. Son was seated, alone, smoking a slim black cigar. Zeffa introduced us. I didn’t know what to say, so I just said the truth.

“You’re the ace,” I told him.

“Thank you,” was all he said. Not grabbing the title, but not disclaiming it, either.

~~~

Ultimately, Andrew’s death just motivates me to focus more (and solely) on something I’ve always cared about: child welfare. I already had a plan in the works for something big I (and my family) would be doing. Those who know me know to what I’m referring. In the meantime, I will mourn the passing of a Giant. A man whose Heart was big enough to be transplanted into all of us.

Writer and psychotherapist Zak Mucha—who I believe shared a very special relationship with Vachss—sums it up: “”The most emotional thing someone could do would be to invest themselves in something, to take a stand,” says Mucha.

Damn right. Mr. Vachss, You Were The Ace.